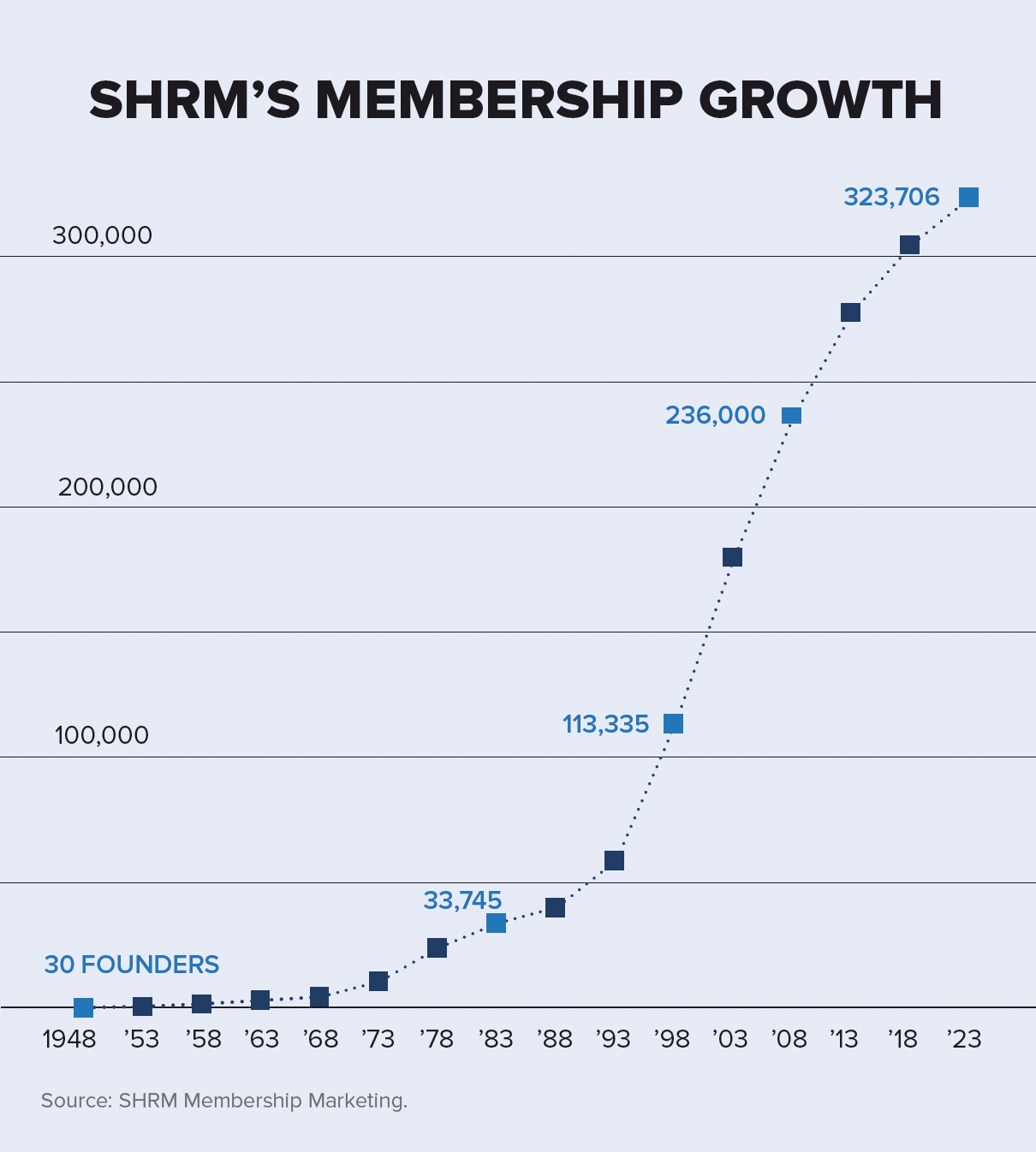

Now more than 320,000 members strong, the Society for Human Resource Management began in 1948 with a handful of dreamers—and a twist of fate.

Share Bookmark i Reuse PermissionsHuman resources is so firmly rooted in the American workplace today that it’s almost impossible to believe there once was no such thing.

But in 1900, the U.S. was beginning to emerge as an industrialized society and the concept of personnel departments simply didn’t exist. Employment decisions were in the hands of front-line supervisors. Company leaders held a general disregard for workplace safety. And the U.S. workforce included 2 million children between the ages of 10 and 15.

To appreciate the history of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) as it celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, it helps to understand the evolution of human resources as a profession.

The first seeds of HR were sown in the early 20th century, as “employment clerks” emerged to select daily help, primarily in factories. But the real genesis of HR was during World War I. A sharp spike in demand for industrial output and the loss of workers to the war effort led to a severe labor shortage. That forced employers to raise wages, focus on recruiting and formalize their employment efforts.

In 1915, only 5 percent of large U.S. companies had personnel departments. By 1920, that figure had jumped to 20 percent. This rapid growth seemingly created a new profession overnight. “Personnel administration” was becoming an accepted term.

The Great Depression of the 1930s led to a slew of New Deal laws that forced employers to get serious about paying workers fairly, keeping them safe and dealing with labor unions, which were becoming prevalent. As a result, personnel departments began instituting formal hiring procedures and creating the first employee handbooks.

During the 1940s and the post-World War II labor boom, more employers needed specialized staff to manage labor relations. Workers’ compensation laws were passed in 48 states, and the power of unions was generating a backlash. Plus, companies were beginning to understand the competitive benefits of treating employees well.

During those years, personnel managers were “starving for information. … We grabbed at anything we could find,” said Mary Hopkins, a management professor in the 1940s, during a recorded interview. Hopkins and several hundred people attended a conference in Chicago in 1947 led by a new group called the National Association of Personnel Directors (NAPD). But attendees weren’t impressed.

“Partway through the conference, we realized this was a con game,” recalled Leonard Smith, a personnel director at the time, in a recorded interview. He noted that anyone who sent $50 to the organization could become a certified personnel director. “So a group of us called a meeting during the conference to find out whether [attendees] were really interested in a professional organization.”

Nearly 30 people sat down and talked about forming a new national association. Within months, the NAPD filed for bankruptcy, opening the door for this new group. The breakaway committee then gathered at the Carter Hotel in Cleveland on Nov. 20-21, 1948, along with a steering committee of personnel administrators from various local and regional personnel associations around the country.

It was at this meeting that the American Society for Personnel Administration (ASPA) was born. The founding members appointed Smith as chairman, Hopkins as secretary and Harry Willett as treasurer. They established committees for budget, membership, conferences and publications. They wrote bylaws and a code of ethics.

Managers at the time looked upon personnel administrators “as a stylish nuisance,” according to Walter Ronner, one of ASPA’s founding members. So this new group set out to create uniform standards for the personnel profession.

On Nov. 21, 1948, Ronner became the first person to apply for ASPA membership and pay the $25 annual fee. Membership that first full year topped out at 92 people; only six were women.

The association’s first goals were modest and included an annual convention, a periodic newsletter and four board meetings a year. Within 10 years, the founders hoped to build an influential group that management, labor and legislators would listen to and respect.

The first Annual Conference was held in Cleveland in June 1949, attracting 67 attendees. The event actually made money—a profit of $72.86.

The group’s political advocacy foundation was established that year, as well, as ASPA formed its first Legislative Committee to decide on the group’s advocacy priorities in Washington, D.C.

SHRM Firsts

Application for Membership

Walter Ronner, Nov. 21, 1948

By 1950, ASPA had grown to 130 members and the group began publishing Personnel News, which would soon become The Personnel Administrator and eventually be renamed HR Magazine in 1990. Now in its 73rd year, HR Magazine would become one of the nation’s longest-running association publications.

That initial issue of Personnel News in 1950 included two open personnel jobs, one for “a young man with some experience” and another for “an experienced top man.” (Job discrimination laws wouldn’t come into play for another 14 years.)

The Society was still functioning under a totally volunteer structure, but it was growing and needed a place to call home. It first established an office at Marquette University in Milwaukee, where then-ASPA President Russell Moberly, a management professor at the school, offered office space and clerical help. In 1956, the board approved the hiring of its first full-time staff member, Executive Vice President Paul Moore, who moved the ASPA offices to Michigan State University, where he worked as a professor.

The 1950s also saw the birth of ASPA’s affiliate system for regional personnel groups, many of which were already in existence. The first affiliate was the Personnel Management Association of San Diego. Today, SHRM has connections with 51 state councils and 583 chapters, all of which are independent groups affiliated with—but not run by—SHRM.

It was around this time, in 1954, that Peter Drucker’s The Practice of Management was published and the term “human resources” was born, adding new credibility to the profession. But HR’s seat at the big table was still a long way off. Upper management was often distrustful of HR and frequently engaged in turf wars to seize control over employment decisions.

As ASPA membership continued to grow (topping 2,000 for the first time in 1960), so did the Annual Conference. Attendance for the event grew steadily for the first few decades: 92 in 1950, 382 in 1960, 1,152 in 1970, 3,000 in 1980, 4,000 in 1990 and 10,000 in 2000. By 2019, more than 18,000 people attended the largest annual gathering of HR professionals in the world.

The association also began to see the value of connecting with the next generation of HR leaders. In 1964, following the success of its first pilot student chapter at Indiana University, ASPA launched a nationwide student chapter program. Today, SHRM hosts chapters at more than 200 colleges and universities that serve as career compasses and networking hubs for students interested in HR.

This period also saw the creation of SHRM’s research arm. Those early bylaws called for the Society “to advance research toward higher standards of performance in personnel administration.” These days, SHRM Research is a worldwide leader in studies focused on the intersection of people and work.

With its increasing successes, ASPA had outgrown its part-time office space on college campuses and needed a dedicated work facility. But where? Sites were narrowed to three options: the Chicago, Cleveland and Cincinnati areas. In 1964, the board decided to lease 600 square feet of office space on 52 East Bridge Street in Berea, Ohio, just south of Cleveland. By the end of the decade, the office would house 10 employees.

More initiatives and staff meant more publications. In the mid-1960s, the association launched the Washington Newsletter, which covered the passage of new federal laws prohibiting job discrimination based on race, sex, age and religion. Another new publication, What’s New, focused on association news.

In 1966, recognizing the need to provide scholarships and support philanthropy work, the association created the ASPA Foundation to mobilize association members for positive change. Today, the SHRM Foundation serves as the association’s 501(c)(3) philanthropic arm, supporting initiatives focused on topics such as mental health and wellness, inclusive workplaces, and military veterans.

As ASPA turned 20 years old, its leaders saw one glaring hole in its services: a defined body of HR knowledge—and a certification program to go with it. After a couple of years of planning, the ASPA Accreditation Institute was born. The first HR certification exam was given to 80 test takers in April 1976, with 82 percent passing. Soon after, the ASPA Accreditation Institute became a separate organization with its own board.

Today, certification is one of SHRM’s core services. In 2014, SHRM created its own certification offerings—the SHRM Certified Professional (SHRM-CP) and SHRM Senior Certified Professional (SHRM-SCP)—which are recognized by employers worldwide. More than 120,000 people are SHRM-certified, which accounts for 85 percent of the HR certifications in the country.

In addition to certifications, SHRM began offering educational programs to help HR professionals build skills and advance their careers. Today, more than 500 in-person, online, recorded and print training tools are available on every HR topic imaginable. All of these training materials and certifications are based on a core set of competencies outlined in the SHRM Body of Applied Skills and Knowledge (SHRM BASK).

In response to a flurry of employee-rights laws enacted in the 1960s, the association hired its first part-time staffer in Washington, D.C., in 1971 to lobby on Capitol Hill. In 1973, ASPA opened its first D.C. office. That same year, for the first time, the association provided testimony in a congressional hearing on pending legislation—the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. The association’s ground-level involvement on this landmark law set a tone for the pivotal role it would play in shaping workplace legislation over the next 50 years.

Today, the SHRM Advocacy Team (or “A-Team”) includes more than 17,000 HR professionals in all 435 congressional districts who are trained to help inform both federal and state legislators on how proposed legislation will impact employers, employees and the HR profession. It’s one of the largest networks of its kind in the nation.

With legislation becoming a growing focus for ASPA, the board voted in 1984 to move to the Washington, D.C., area. Board members cited the need to “create a national presence” and to “have more consistent engagement” on workplace public policy. The organization leased space at 606 North Washington Street in Alexandria, Va., just across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. ASPA eventually purchased the building, which would remain the Society’s home until 1997.

Even during this expansion of professional staff, ASPA was still chugging along mostly on volunteer power. In 1984, ASPA hosted its first Leadership Conference to bring together volunteers from around the country to learn about the organization’s goals and initiatives. That conference expanded over the years and was eventually renamed the Volunteer Leaders’ Business Meeting.

As ASPA approached its 40th anniversary, “personnel” was becoming an antiquated word. “ ‘Human resource management’ was the term everyone was using, so we thought, ‘Why not incorporate it into our name?’ ” said 1980s board member Wanda Lee.

Attempts were made to rename ASPA during the 1960s and 1970s, but the board rejected them each time. Now all agreed the name was just too outdated. Different names were discussed, including the Human Resource Management Society and the Society for Human Resource Professionals.

In the end, the board voted 8-1 to change the name to the Society for Human Resource Management, effective Sept. 1, 1989.

With the new name came a new focus. That year’s board meeting concentrated on the increasing need for HR to become a “strategic partner” in corporate America—the first time that phrase appeared in board minutes.

In the 1990s, SHRM’s influence continued to expand internationally, including bilateral meetings with French and British HR societies and a USSR People-to-People Tour. To unify workplace positions on the continent, SHRM, along with HR groups in Mexico and Canada, formed the North American Human Resource Management Association. In 1997, SHRM created its first global membership category.

At home, SHRM announced a new Diversity Initiative, but not without controversy. Some critics argued that expanding diversity should not be the duty of HR. The initiative grew, however, and SHRM created a name for itself as a leading organization in this emerging field. In 1996, SHRM held its first Workplace Diversity Conference, which is now known as the INCLUSION conference.

To this point, members had received all SHRM publications and information through the U.S. mail. That changed in 1994, when SHRM became one of the first associations to establish an online presence. It launched an online forum on Prodigy and then, eight months later, abandoned it in favor of its first website, www.shrm.org. During that year’s Annual Conference, SHRM staff offered demonstrations of the website, which gave some attendees their first opportunity to try a new thing called the Internet.

The SHRM website and e-newsletters are now among the most popular member benefits, offering daily HR news, webcasts, in-depth articles, sample policies, online tools and links to all SHRM services. SHRM’s social media community (LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram) boasts more than 1.3 million followers.

In just a few years, SHRM had outgrown its headquarters. In 1997, the staff moved into its current building at 1800 Duke Street in Alexandria, Va., and three years later added a second building next door, creating a SHRM campus. As the century drew to a close, SHRM celebrated its 50th anniversary with membership topping 130,000.

The 21st century would lead SHRM to even more global growth. Today, SHRM has offices in eight locations around the world: Virginia; Washington, D.C.; two offices in California; three in India; and one in Dubai. Just last year, SHRM President and Chief Executive Officer Johnny C. Taylor, Jr., SHRM-SCP, delivered a keynote address at a United Nations town hall on the role of business in sustainable development.

SHRM Government Affairs has become the go-to source for all workplace legislative and legal issues, leading to positive changes in federal and state laws on health care, immigration, family leave and more. That reputation was punctuated by a visit from President George W. Bush to SHRM headquarters on Feb. 12, 2003. SHRM’s focus on “Policy Not Politics” means the Society doesn’t have a political action committee and never endorses (or financially contributes to) political candidates.

The past decade also saw the birth of the SHRM Executive Network, a private community of SHRM members catering to the unique business and professional needs of CHROs and other HR leaders. SHRM also launched Enterprise Solutions, allowing corporations for the first time to become SHRM members and leverage the Society’s resources to optimize hiring, boost engagement and maximize inclusion.

In 2020, the HR profession faced perhaps its biggest challenge ever—and embraced the opportunity to shine. The “seat at the table” debate effectively ended, as the COVID-19 pandemic gave HR professionals the opportunity to lead their organizations through every phase of the public health crisis.

As organizations leaned on their HR professionals during the pandemic, HR leaned on SHRM. The association rolled out thousands of time-sensitive articles, webcasts and checklists on everything from vaccine mandates to virtual onboarding. Traffic to SHRM’s online publications spiked by nearly 50 percent in the year after the pandemic began. SHRM partnered with the White House to host webcasts featuring the latest guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And while the pandemic forced the first-ever cancellation of SHRM’s Annual Conference in 2020, the event offered a virtual option in ensuing years and roared back in 2022 with a packed live venue.

Over the past 75 years, SHRM has grown to become the voice of all things work. The founders’ vision remains essentially the same—to elevate HR and build a world of work that works for all. Today, SHRM’s more than 320,000 members impact the lives of more than 115 million workers and families globally.

As the pandemic eases, HR is being pushed to answer one of the biggest questions of our time: What is the future of work? For SHRM, the march toward our 100th anniversary will focus on helping members solve that critical and complex challenge.

Patrick DiDomenico is managing editor of SHRM’s Executive Network publications.

Photographs from ANTONIOMAS / SHUTTERSTOCK and HAROLDGUEVARA / SHUTTERSTOCK.

SHRM’s Top Executives Through the Years

Brice joined the American Society for Personnel Administration (ASPA) as a member in 1950 and served as volunteer president in 1956 before becoming executive vice president nine years later. He passed away in 1985.

The Detroit native had 23 years of HR experience before being named CEO of SHRM. He was responsible for moving the organization to Alexandria, Va., from Ohio in 1984 and later changing the name to the Society for Human Resource Management, as well as growing membership by more than 60 percent during his tenure. After leaving SHRM, he taught in the business school at Florida Atlantic University for seven years. He passed away in 2015.

Losey had 30 years of HR experience prior to his arrival as CEO at SHRM, and he is credited with tripling membership to more than 150,000 and boosting revenue sixfold. He served on the boards of several industry groups and wrote frequently about the profession, including several books. SHRM’s annual award that carries Losey’s name honors lifetime achievement in human resource research. Losey lives in Florida and continues to speak on a range of HR topics.

The organization’s first female CEO, Drinan had 20 years of HR experience, primarily at BankBoston Corp., before arriving at SHRM. While her tenure was brief, she focused on enhancing SHRM’s position among CEOs and guided the organization through the trauma of 9/11. She later became president of Simmons College in Boston for 12 years and is currently interim president of Cabrini University in Radnor, Pa.

Susan R. Meisinger, 2002-2008

After serving as a deputy undersecretary in the Department of Labor, Meisinger joined SHRM in 1987 and rose through the ranks for 15 years before becoming CEO. An attorney by training, Meisinger grew both SHRM membership and revenue significantly during her tenure, and opened offices in India and China. She currently serves on several boards and is an accomplished writer. SHRM’s annual Fellowship for Graduate Study in HR award is named for Meisinger.

Lawrence “Lon” O’Neil, 2008-2010

O’Neil served a relatively short term as SHRM’s CEO but was an effective bridge between two long-tenured CEOs. Prior to joining SHRM, O’Neill was CHRO of both Bank of America and Kaiser Permanente, as well as a managing partner at Heidrick & Struggles. O’Neil is retired and lives in Northern California.

SHRM was Jackson’s “second career” after spending more than 30 years in finance positions at Howard University and in public accounting. He initially joined SHRM as CFO before becoming CEO and was responsible for launching the competency-based certifications—SHRM-CP and SHRM-SCP—and growing the number of SHRM-certified professionals to more than 100,000 worldwide. Jackson now runs a family-owned real estate development firm and serves on the board of the Myers-Briggs Co.

Since his arrival as SHRM’s current CEO, Taylor has overseen the expansion of SHRM membership to more than 320,000, the growth of revenue by more than 50 percent, the creation of the SHRM Executive Network, the expansion of SHRM’s conference business, and the acquisition last year of Linkage Inc. and the CEO Academy, among other accomplishments. Taylor has extensive experience as a CHRO and as general counsel at a range of companies and law firms. He served as CEO of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund prior to joining SHRM and is the author of Reset: A Leader’s Guide to Work in an Age of Upheaval (PublicAffairs, 2021). Taylor is a board member of several private-sector companies and is a frequent conference speaker.